Nearing Nine Years Since Year Zero.

We'd need a radical restructuring of the Canadian economy, dramatic immigration reform and a complete retooling of the federal state to make things right again.

Is anybody in Ottawa really being honest about this?

Maybe it’s because it would be too incendiary, too alarmist to come right out with it.

Maybe there’s something I’m not seeing, but one thing I know I don’t see is evidence of a serious national conversation about the state this country is in, and the direction we’re headed, which I was on about in my column in the National Post this week: The inability of Canadians to simply afford a roof over their heads isn’t just some one-off policy conundrum. It has become a chronic condition of life in this country.

Anything could happen and nobody here is a clairvoyant but it seems fairly certain that Justin Trudeau is a dead man walking. The next federal election has to be no later than October 20 next year, and the latest Nanos polling shows nearly half of Canadians don’t want to wait. They’ve had it.

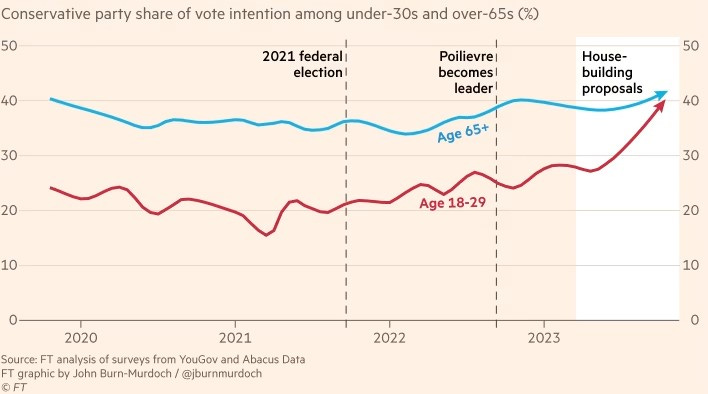

The Conservatives’ Pierre Poilievre should be credited with tapping into the hopelessness and pessimism that overshadows the outlook of so many Canadians. Poilievre’s focus on the way affordable housing has been put out of reach, especially for Canadians under 30, has earned the Conservatives astonishing returns.

It’s too late for mere policy overhauls. We missed our chance.

It’s comforting to think that Poilievre’s “common sense” remedies - slashing taxes, gutting the bureaucracy, disarming the “gatekeepers” and strongarming local governments to build or else - will turn things around. I’m not comforted, because we’re well past the point when this approach would have made a difference.

That point was around, say, 2015. But that was Year Zero, and look what’s happened since then:

There are two things you should notice in that data.

The first is that the gap between actual income and house prices in Canada started widening about 20 years ago, so the problem is not just the Trudeau government’s nine-year contribution to inflation by way of deficit spending and the carbon tax and so on.

The second thing to notice is that while the gap’s been there for a while, it really took off when Team Trudeau came to power.

In my Post column I pointed out that the crippling economic dysfunction known as “housing unaffordability” is worse now than at any time since the early 1980s. That’s the Bank of Canada’s assessment. I referred to the perfect storm of house-bubble prices and sky-high interest rates 40 years ago. Here’s what it was like back then, and what’s happened since:

Supply and demand, and demand and demand and demand.

So, “build, build build,” right? Look at those deliciously low mortgage rates we’ve been blessed with in recent years. It’s simply a matter of ensuring that supply meets demand, right?

Wrong.

Here’s what things were like in 1981 in Vancouver, the most expensive housing market in Canada: "So many houses are now for sale in Vancouver that it takes nine volumes to list them all," CBC reported back then. All the supply you could ask for. And yet, merciless housing-bubble prices.

My point: it was once possible to remedy crises like this by jimmying with supply-demand dynamics, interest-rate policy and tax incentives. Those days are long gone. “Housing unaffordability” has become a chronic disfigurement of Canadian life. It’s not just some treatable ailment, some readily remediable, temporary, ephemeral problem.

It’s structural. It’s what we have allowed our country to become.

It’s money that matters.

Meanwhile, as the analysts at Better Dwelling point out: “After decades of telling the public that low rates make housing affordable, Canada’s central bank is declaring, whoops! Bank of Canada (BoC) research shows decades of low rates did not make housing affordable. In fact, it had the opposite effect — increasing the size of mortgage debt.”

It’s gotten so that while migrants are flocking to Canada, Canadian citizens are leaving. It just costs too much to stay: “The latest data shows emigration rose 3 percent higher to 32,026 people in Q3 2023. That number is astronomical, and hard to appreciate just on its own. Over the past 73 years of data only three years have seen larger quarters—2016, 1967, and 1965.”

The reduction of housing stock to speculative property holdings is definitely an element of structural failure. Residential property investment has reached 7.8 percent of Canada’s gross domestic product, nearly a percentage point higher than it was in the United States in 2006 when the American house of cards collapsed.

But that’s doesn’t account for it all. In my column I pointed out that crazy high immigration rates don’t explain absolutely everything either. But let’s please be honest.

Within two years of Trudeau waltzing into the Prime Minister’s Office in 2015, more people were arriving in Canada than any year since 1912.

In 2022, 822,866 people arrived in Canada, twice as many as 2019, the largest influx in half a century. We could always say, well, no biggie, that just makes up for the dip in arrivals during the Covid shutdowns.

But between the summer of 2022 and last August, nearly 700,000 “non-permanent residents” arrived in Canada on top of the 400,000-plus permanent residents who showed up in Ottawa’s official immigration counts. Statistics Canada reckons there are now roughly 2.5 million non-permanent residents in the country, which is close to the entire working-age population of Alberta.

If this reflects a federal immigration “policy,” it’s crazy.

The last time I took a long look at this state of affairs I concluded that matters were much worse than Poilievre was letting on, and worse was yet to come. See: 'None of them are a good option'? and in the Post, Voters need more from Conservatives than snappy slogans. I stand by that judgment.