Journalism's Golden Age: Where Did It Go?

The Internet! A world of news literally at our fingertips! Except that never happened, or if it did, the gleaming epoch is already over.

We’re back today with Marc Edge for the Real Story guest series A Platform for My Enemy. First instalment was Monday, The News, Past Tense, and today is Marc’s The News, Present Tense.

That first instalment kicked off one of the liveliest debates (and maybe the most bruising) among Real Story subscribers (a paying sub brings you into the conversation). No paywall for this series, but you know what to do:

If you want to witness the immolation of conventional journalism in real time you can do just that this week (headlines suffice, click the links later if you like): Lawyer says residential school denialism should be added to Criminal Code, Canada needs legal tools to fight residential school denialism, report says, or A hasty, pretend ban on denying a residential school 'genocide' is inevitable. It’s a rapidly rising crescendo in a neo-Stalinist comic opera that went into high gear with this: NDP MP calls for hate speech law to combat residential school 'denialism'.

I’ve got a piece about all this in the National Post and the Ottawa Citizen that will be online shortly (and I’ll be back in this newsletter with more on the subject shortly). I really didn’t want to get dragged back into it but I’ve been in the eye of this particular storm ever since I wrote this 5,500-word reconstruction of the Trudeau government’s months-long, state-incited media paroxysm of 2021: The year of the graves: How the world’s media got it wrong on residential school graves. Long story short: When narrative replaces facts: The furor over my 'The year of graves' feature illustrated perfectly what the piece was about.

The Real Story archives contain a great deal of backstory to that national psychotic episode. The Liberal government and a phalanx of pseudo-apparatchiks are now intent upon revisiting the whole thing on this country, making it a permanent state of Official Truth and Thoughtcrime. Whether the attempt succeeds or fails, this is a very big deal, and it’s not captured by thoughtful analyses of the state of the “news” of the sort my frenemy and series author Marc Edge is writing about in Real Story this week.

Put as succinctly as possible, it’s this. Along with the historic bleeding out of conventional journalism, we’re living at a moment in time when all the disciplines we’ve relied on for centuries to establish broad societal agreement about what constitutes the truth are being deconstructed before our very eyes.

This is a time of deep epistemic crisis — the collapse of consensus about how to go about the work of determining what’s true and what isn’t. In its place, a state-enforced substitution of knowledge with belief. In the blink of an eye we’ve gone from “facts don’t matter” to “it doesn’t matter that facts don’t matter.”

This is absolutely fatal to the functioning of liberal democracy.

Anyway, a year ago I wrote in the Post: It’s not for nothing that there’s a great deal of skepticism about the Trudeau Liberals’ online streaming law, their enthusiasm for regulating speech on digital platforms and their $595 million bailout of Canadian news organizations, of which the Post is a beneficiary.

Just six weeks ago, amendments to the Broadcasting Act received royal assent. Bill C-11 stipulates that online streaming and on-demand services are a class of broadcasting subject to regulation by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). This week, Bill C-18 inched closer to Royal Assent when Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez accepted most of the Senate’s proposed amendments.

Bill C-18 would make Google and Facebook compensate news organizations for posting links to their work, obliging the mammoth tech platforms to enter into negotiations with news organizations ranging from the CBC to local weeklies and campus radio stations. Facebook has threatened to block Canadian news links. Google says it’s considering the same.

Among the Senate amendments Rodriquez accepted was this odd one: the law comes with fines for leaking media organizations’ confidential financial information. Weird.

Anyway. . . on to the next in the series, A Platform for My Enemy.

Part Two: The News, Present Tense

by Marc Edge

Local news coverage in Canada suffers from what Harold Innis called space bias. The legendary University of Toronto political economist came to study communication late in his career, which was sadly cut short by cancer in 1952 when he was just 58. By studying how empires communicated throughout history, Innis came to realize that the dominant medium of each had a bias toward either enduring throughout time or expanding across space. His research was continued after his death by his U of T colleague Marshall McLuhan.

Writing was pioneered by the ancient Egyptians, who literally carved their hieroglyphics in stone. This helped their empire last for 3,000 years, but it didn’t get very far. The Romans innovated by writing on more portable papyrus pounded from the reeds of the Nile delta. By using this more space-biased medium they were able to rule Europe and North Africa for 1,000 years.

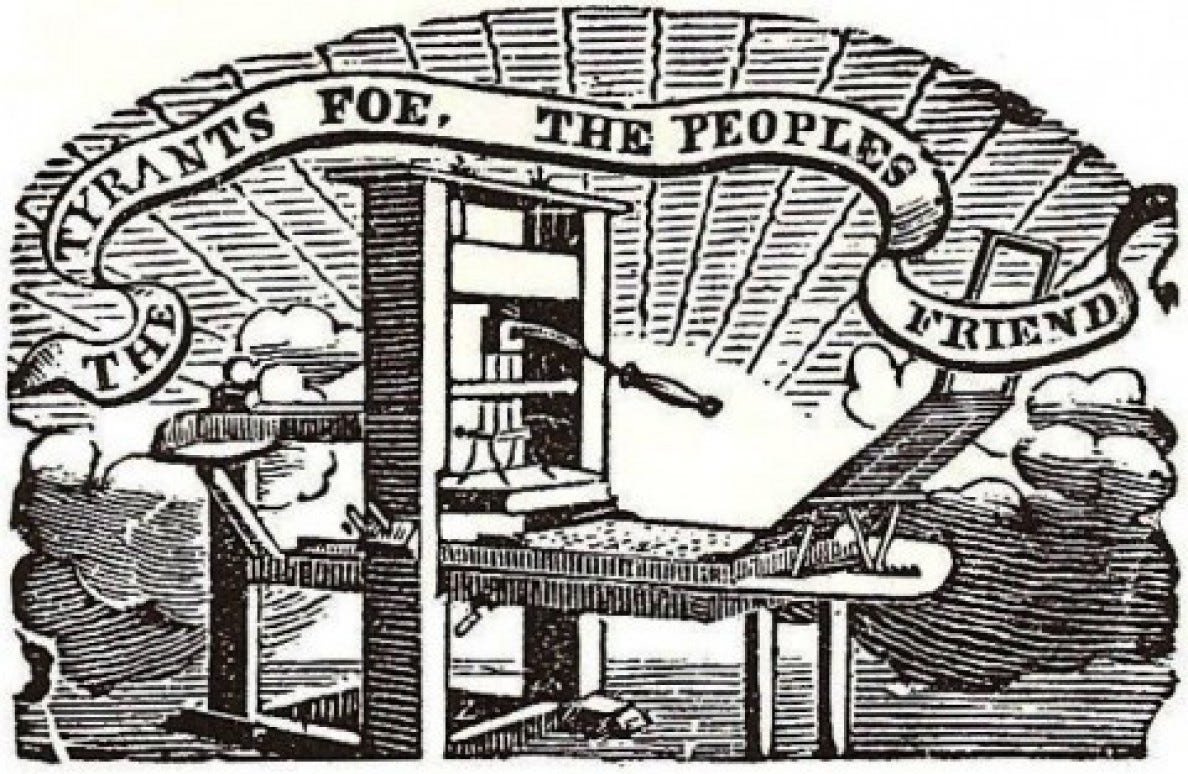

Printing on more plentiful paper allowed for the mass reproduction of texts, and more importantly, accurate maps and charts. This medium allowed the British empire to expand around the world. Their empire lasted about 300 years. Broadcasting began a century ago, allowing the American empire to eventually circle the globe with satellite transmission, but that state of affairs is already waning.

The ultimate space bias has been brought about by the Internet, which can be argued to have created a new golden age of journalism. We now have a world of news literally at our fingertips! The irony is that we often get little news from where we actually live.

Introduction of the so-called “information superhighway” in the 1990s was always supposed to spell doom for old media, but few would have guessed 30 years ago that a search engine and a social network would soon dominate media by revolutionizing marketing.

The downside of the Internet’s space bias has been a diminishment of the local. No longer does the Vancouver Sun publish editions of 120 pages and more on Saturdays. Last Saturday’s paper was 50 pages, much of which was filled with copy (that’s what we journalists call news stories) from other newspapers in the Postmedia chain, plus special advertising features. A typical weekday edition of the Sun might be 28 pages, half of which comes as a National Post section.

The Sun and most of the other major metropolitan dailies from coast to coast are now 98 percent owned by U.S. hedge funds which have been bleeding them dry for the past 13 years by also holding most of their massive debt. While all newspapers have had to make layoffs and cutbacks in the face of plunging ad revenues since the last recession, Postmedia’s dailies have been hit twice as hard.

Those special advertising features I mentioned are what we now call branded content or native advertising, which is the latest thing in newspapering. It’s very effective because it is designed to look like news - studies have shown that most readers can’t tell the difference. All the big dailies run this content, including the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star.

For decades, newspapers ran so-called advertorials, which blurred the line between advertising and editorial, such as special sections for real estate, travel, and cars. Branded content takes the concept to another level of advertising sophistication.

Local broadcast news is also just a shell of its former self. CKNW radio’s major newscast at 6 p.m. in Vancouver is now a simulcast of the evening news from the local Global Television station. Since both are owned by Corus Entertainment, they save money by carrying the same content. Money is again the missing ingredient here, of course, because the advertising dollars that once went to old media now flow mostly to Google and Facebook. The CBC is all that some communities have left, thanks to its taxpayer funding.

And don’t even get me started on the sorry state of Canada’s magazines. Maclean’s was once a weekly newsmagazine that featured some of the country’s best writers [thank you Marc - ed] and covered politics in depth, but it was recently disembowelled and rebranded as a monthly lifestyle magazine for Millennials.

But what about the Internet? Wasn’t it supposed to pick up the slack in the transition to an all-digital news future?

Yes and no. There has certainly been a proliferation of news websites, and some even do investigative reporting on occasion, but on nowhere near the scale once seen in “old” media. Most online-only publications are more like magazines, with many being vanity projects for the rich, coming from their point of view, or even covering only one issue, however worthy it may be, such as “the environment.”

Few of these online publications provide the kind of comprehensive local reporting once seen in newspapers. But some do. A hotbed of such journalism is actually Halifax, where the website allnovascotia was founded in 2001. By 2013, it had more than 7,000 subscribers paying $39 a month, which was enough to employ 15 journalists covering business and politics. It has been so successful that it expanded to Newfoundland and Labrador in 2016, New Brunswick in 2019, and Saskatchewan in 2021.

Halifax is also home to the online Examiner. Investigative reporter Tim Bousquet started the Examiner in 2014 after leaving the Coast alt-weekly after seven years as its news editor when his bosses asked him to write branded content. His coverage of the pandemic and the 2020 mass shootings in Nova Scotia doubled his subscribers, allowing Bousquet to hire two full-time reporters.

On the west coast, another great source for independent investigative journalism is Bob Mackin’s The Breaker News.

In most of Canada, however, local news coverage is sadly a shell of its former self. Most city council meetings go uncovered, school boards even less so. The federal government has waded in since 2018 with its Local Journalism Initiative, which spends $10 million a year, ostensibly to fund reporting in under-served communities.

Then there was the five-year $595-million federal bailout that began in 2019, which has been keeping Postmedia afloat recently but runs out this year. The feds funded Postmedia to the tune of $9.9 million in its last fiscal year, but even then. Postmedia’s operating earnings of $13 million came nowhere near covering its more than $30 million a year in debt payments.

Bill C-18 (see Terry’s introduction to this instalment in the series) would force Google and Facebook to fund news media instead, but the digital giants have threatened to quit carrying links to Canadian news stories rather than pay for the privilege. If that happens, Ottawa would again be implored to bail out the newspaper industry or to come up with a better way of informing Canadians about their own communities.

The possibilities range from a dystopian info-hellscape dominated by disinformation, government news and paid content, to best-case scenarios that might not be utopian, but could help fill a need.

NEXT UP on Friday: What fresh hell awaits us?

(You can read all about Edge and what he has to say for himself here. And of course he’s Marc Edge, not March Edge, as an early version of the newsletter misspelled his name). If you want to support journalism of the kind you find here at The Real Story you should subscribe if you don’t already, and make it a paid subscription to keep this newsletter going.

Really enjoying this series - thank you for bringing in guest PoV's. As a former Vancouver journalist (community papers and BIV) I think there are two things often overlooked in this conversation:

1) The so-called 'Golden Age' of Journalism - the post-war period until Y2K, roughly, was able to exist for a key reason: massive profit margins allowed for significant organizational breathing room and that resulted in maximum independence for editorial departments. As soon as those profits were squeezed, the owners had to cut-back, reduce independence or both.

2) The Golden Age is actually a relatively short period of time in the history of the news business. Pre-war and earlier journalism was surprisingly similar in form and function as what we're seeing enter the 'news' space today. It's possible the Golden Age was the anomaly, the norm is this.

Lastly, as a former business journalist I can say one thing you get good at is analyzing businesses. It was hard not to analyze the industry and media companies I worked for/interacted with when I was in the newsroom. It was obvious to me in 2011/12 that if I wanted to get ahead in life (you know, own a house one day), sticking it out in the news business was a poor bet. I love the news business, still do but a lot of the good talent left for some basic reasons and that's undermined the business as well (No, I don't count myself among the 'good talent').

With Dad at Stanford during the development of the internet, a Defense Dept. project to provide secure, redundant communication channels during an enemy attack, the irony that it became the major channel to breach security, is overwhelming.

For a brief period it was very informative in being able to translate the emails of sites such as the Brigades of the Martyr Izz el-Deen al-Quassam "militants" lament that their 2011 anti tank missile attack on an Israeli school bus at the end of its route had not killed a full busload of kids, only a single student remaining at the final stop, not in the frame of most news coverage.

My ideal of impartial or broad spectrum news coverage was reversed when the CBC replaced BBC Northern Ireland coverage with their own stringer, whose lionization of Gerry Adams and contempt for the "British" was clearly evident in her delivery. Her bio details disclosed that she came from "a strong Republican family", had fundraised for Sinn Fein in Boston and believed that good reporting demanded a "passionate personal point of view". When Tony Burman initially showed interest in my concern but eventually responded that he had "full confidence" in her, I decided that bias was really inevitable and a clear, open declaration, (which as others have pointed out, was the norm for newspapers for decades past) was the best that could be hoped.

When Guardian Editor Alan Rusbridger in 2015 announced that the Guardian, having sold the profitmaking Autotrader, was no longer a "newspaper" but becoming "a campaigning organization" against "Climate Change" and would no longer publish anything contradicting "consensus science" it was at least openly inverting C.P. Scott's iconic 1921 editorial principle of dealing fairly with opposing views. But establishing the "Covering Climate Now" consortium which now coordinates "urgent climate stories" to ensure that all 500+ media partners distribute a uniform message to their 2 billion audience, is without suitable notice.

Like the old K-Tel guarantee that your " Best of 100 classical works" would contain "no unfamiliar music", it seems to be profitable.