A Death in the Family

Robert Rex Raphael Murphy: A proposition as to the origin of his style, his standpoints, and how he managed to survive among the mainlanders.

November 21 2011

Terry, I very much enjoyed that yesterday, and appreciate your

coming in and taking all that time. We have had much fine responsecabon,

and as far as I am concerned it is one of the very best programs we have done.

That's because of the guest and his book.

Cheers. Rex

Had a fun evening at Hillel. Met some people who know you.

That’s the first entry in an email thread that carried on intermittently between us for several years, most of which would be incomprehensible to pretty well anyone because it’s as though we corresponded in code. I’ll explain below.

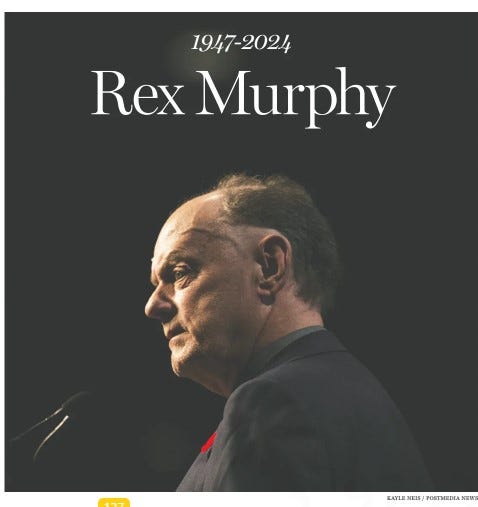

Today’s newsletter was going to be a fairly dense account of what I’ve been up to in the beats I cover. Let’s just say it’s been a bit overwhelming. I was told of his death Thursday but it was strangely unnerving to find my latest, From Ottawa to Vancouver, Canada capitulates to the anti-Israel mob, on the front page of the National Post below this: Rex Murphy, the sharp-witted intellectual who loved Canada, dies at 77.

‘We’ll rant and we’ll roar, like true Newfoundlanders.’

About that first email, above: At the time, Rex was the beloved host of CBC Radio’s Cross Country Checkup, and he’d invited me on to talk about the book I’d just written, Come From The Shadows. He ended up having me on for the entire show, even sticking around to take calls from listeners and so on.

The book is about Afghanistan, drawn from the time I’d spent mostly “outside the wire” and from my inquiries into the deep chasm between what the Afghan people had to say about their predicament, and what come-from-aways called “the war.” Rex noticed the important thing.

Year after year, in poll after focus group after opinion survey, the overwhelming majority of Afghans were unambiguously in favour of the NATO intervention, while respectable “progressive” opinion in the United States, Canada and much of Europe was overwhelmingly against it.

What struck Murphy about the book wasn’t just its deparature from elite “progressive” consensus but its attention to ordinary Afghans and the long history of their struggle for something approaching democratic normalcy and pluralism.

This is the important thing to understand about Murphy, whose death is being mourned across Canada this weekend: Far more than politics, “conservative” or otherwise, what most concerned Murphy was ordinary people and how they were getting on.

He loved Newfoundlanders and he loved ordinary, working Canadians. Far more than his distinctive, lavishly ornamented sometimes endearingly garish writing style, that’s the thing that people loved about Rex. He was one of them. He loved his readers and his readers loved him back.

The other thing about Murphy is that he was blessed with that rarest of qualities in Canada’s punditocracy: he was a genuinely interesting person. When he showed up on the national scene in the 1990s - which is to say among the Upper Canada nomenklatura - he was like no one else around him.

He was a proper outport boy, like a figure out of I’s the B’y. He was also a Rhodes scholar who’d studied law at Oxford University’s St. Edmund Hall. He was downright exotic in high-society Toronto, and for all its current boasting about racial and gender “diversity,” Canada’s establishment media remains marked by a dreary sameness.

Rex never romanticized outport life, understanding that the lot of the swilers and the fishermen was perilous drudgery. He couldn’t have slaughtered a mouse, but he was rightly enraged by the celebrity environmentalists having their photographs taken while cuddling with baby seals on the ice flows, decades after the taking of whitecoats was forbidden by law in Canada in 1987.

He also understood the swiling to be a perfectly sustainable endeavour. I was in complete agreement with him on that point. Last I looked, Fisheries and Oceans assessed the Northwest Atlantic harp seal population as “healthy and abundant,” roughly 7.4 million animals. The seal hunt was never a danger to the harp seal population, and properly undertaken it was a humane if bloody business.

We would make fun of ourselves in conversation about this. It was all a great fuss about ice weasels, or sea badgers. It’s not clear from our emails which one of us came up with which of those terms, but it wouldn’t have been like Rex to call them seals and be done with it.

January 11 2013. It's a damnable shame you're not closer or we could have a long long chat - I would provide liquids (not soup).

It was never a meal, almost always “grub.” It was never whiskey, always spirits, liquids, potations, libations, or “the necessary.” We never did raise a glass in person, despite our efforts to make our travels coincide in one place or another.

Our very own Myles naGopaleen?

There was nothing dreary about Rex, even when he was in a dreary mood. To his dying days, there was no one else like him. And this remained so, despite the oddness in the contrast between his stature as a major public figure and the sparseness of anything that might have shed light on his private life.

Here’s something peculiar: I’ve been scouring the various articles and tributes since his passing and I can’t find evidence anywhere of a thing necessary to any proper obituary, which is the date of his birth. It could be that I missed something but all I see is ‘Rex Murphy, born in Carbonear, Newfoundland, 1947, died May 9, 2024.’

I did come across a 1996 article about him in Macleans magazine which referred to his birthdate as “the subject of dispute and a complex tale” but the article shed no further light on the matter.

In our correspondences there is nothing especially illuminating from the first couple of years, except perhaps the consistent kindness of his notes of encouragement, even where we’d taken what might have seemed like the opposite sides of some dispute.

Where things take the turn that I think explains a great deal about the man is right here, on March 19, 2013: Terry, have you read The Best of Myles (columns) or The Third Policement - Flann O'Brien. . . If you haven't go online (ABE is good) and get them. . . I think you'd find them congenial and of the best.

Me to Rex: I believe I possess absolutely everything written by Flann O'Brien (aka Myes naGopaleen aka Brian O'Nolan) and so on.

Rex: Well, we're friends for life, I think I have him memorized .. even have a first edition of Third Policeman, and, a vintage paperback copy too. . .

This is followed by a back and forth, citing passages from O’Brien’s various works. Me to Rex: We are engaging in dangerous behaviour, Raphael. This could go on forever.

It did go on like this, more or less without exception.

How to explain Professor De Selby?

Even on the occasion of certain stories that will leave lifelong scars, he’d have a way of cheering me up, but he’d do so in a manner that requires deciphering that code I mentioned.

About the drowned child on a Turkish beach who changed the way we talked about Syrian refugees, for instance, it was my misfortune to have broken the story. In the Post and the Ottawa Citizen I wrote about its initial impact here: Little Alan Kurdi and the one photograph that mattered.

This is what Rex wrote in the Post: Sheer scale can numb. Perhaps this one photograph of Alan Kurdi will break the cycle. All our politicians should have the decency to admit that their opponents — on the human level — are at least as compassionate as they are.

An email from me to him, September 4, 2015: God love you, Rex.

Rex to me: Oh, it's up early ... appreciate the note, but the thanks go in the other direction. . .Charge on. And remember always De Selby.

The following should give you some idea about what is necessary to know in order to understand the “De Selby” reference.